The welcome warmth of March’s arrival presented an opportunity to get my hands in the soil. Doing so connects me. This dirt, a living system beneath our feet, holds memories. It tells stories. Once marked by the footsteps of the Aspetucks, led by Crecroes, who knew the rhythms of this watershed, stewarded its forests, and lived as a part of the land.

Then came the colonizers, with firearms and deeds, burning bush and long-lot claims. This was not the discovery of a ‘new world,’ but an occupation and dispossession of an entire way of being. Progress followed, yes—but at a cost, a debt. Rivers that once ran free now bear the scars of industry. The forests still shrink beneath the relentless creep. But here, in this soil, native wildflowers will replace an invasive species.

The Mill River, tracing time in the soil’s sediment and stone, shaped and sustained life on this land. Change came slowly—land shifting grain by grain, tree by tree, season by season. In rhythm with the natural world: steady, adaptive, regenerative. The Aspetuck people followed its course, knowing its cycles, its seasons. Later, it powered Easton’s early industries—as grain mills, and sawmills cutting lumber, shaped a new kind of life here. Though its flow has been altered by man, the river persists, a witness to the past and a guide for what comes next.

Just as water slowly carves the land, so too does time shape our relationship with it. But not all change follows nature’s rhythm. Some forces do not shape, but rather bend to the point of breaking, like us humans. The multiple interrelated crisis of our time—ecological collapse, income inequality, mass migration, war—all of these are symptoms of an underlying issue. The result of an extractive system with a fundamental flaw, one that makes it incompatible with life. We feel this too, this growing tension. We know something is amiss, but what?

The land remembers. The rivers flow, carrying the lessons of those who came before us. It is up to us to listen. One way to do so is by slowing down. As spring approaches, consider pausing the mower and letting nature grow. Listen to the land. What can you hear when you allow nature to regenerate itself once again? Listen to the pollinators returning to spring flowers.

Like the downed trees that feed the forest floor, we too will persist, not by resisting nature, but by regenerating with it. Our greatest strength is community, and as tensions rise, we should remember: the forces that look to divide us hold power only when we allow those divisions to take root.

As neighbors, our roots are more intertwined in the soil that filters our watershed than our limbs exposed to their storms. True resilience comes from flexibility, connection, cooperation, and shared stewardship. The error in our ways has been treating nature as if we were separate from it. In truth, we are just a part of a beautifully complex living system.

For something new to emerge, we must recognize our place in the sacred circle of life. We are not separate from this land, from each other, from Crecroes and the living systems that sustained his people and now ours.

We should come to Earth’s table in a good way—with humility, reciprocity, and understanding that no one thrives unless we all do. A free future will not be built by force, but by restoring balance, recognizing interdependence, and listening to the wisdom already embedded in the soil and in each other.

Therefore, we should pledge not just to acknowledge the land and its history, but to reweave the fabric of our reality with networks of community, compassion, and care that have always existed beneath the surface, waiting to emerge.

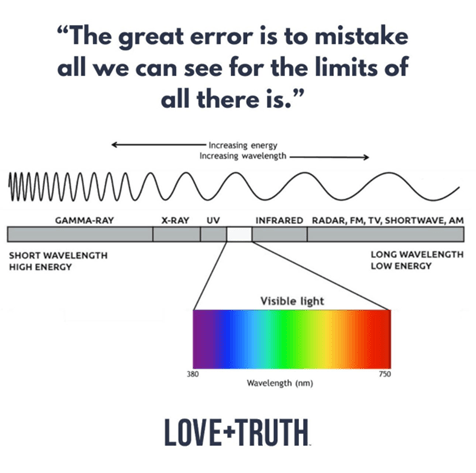

Like the vast spectrum of light we cannot see, there is more to our shared existence than meets the eye. From the AM radio waves in your car to the therapeutic gamma rays that once coursed through my body in treatment, it’s all part of the same spectrum. Unseen, yet undeniably real.

Likewise, there are realities we struggle to perceive, hidden not by nature, but by the constraints of our own making. To navigate the challenges ahead, we need to recognize what is right in front of us. Unseen not by our inability, but by the synthetic limitations of narrow perspectives and outdated systems. A reductionist worldview—one that breaks everything into isolated parts, severed from the whole—prevents us from seeing the interconnections that sustain people and planet alike.

Take the invasive burning bush recently removed from this* land. For years, it served a purpose, providing privacy and fall color. It was an ‘easy’ landscaping solution, planted decades ago. But beneath its ornamental appeal, it was a smothering force. A highly invasive species, its fast growth easily outcompetes native species and disrupts local ecosystems near and far. It was a shortsighted decision, logical within a narrow frame of thinking, but flawed when seen in the broader scope of things.

By removing the burning bush, I am not simply removing a plant but rather allowing the land to return to its natural rhythm. I am stewarding the land to make space for native species to return, for pollinators to thrive, and for balance to reestablish itself.

This is the work we need to do, not just as individuals, but as a community. To see beyond what is convenient. To question assumptions that no longer serve us. To replace what suffocates life with that which sustains it.

If we are willing to do that, if we are willing to shift our vision to what has been unseen, then resiliency will follow. Just as the land regenerates when given the chance, so can we. If we fail to recognize this broader reality, if we allow short-term greed to dictate our long-term future, then, even the wealthiest will find their grandchildren left not with healthy soil, but dust.

We can choose differently. If we reconnect with the land as it was meant to be, we can leave them with something better, renewal.

*We do not own land, rather, we borrow it from future generations.