As Earth Day approached and spurred on by an email from Mrs. Fox Santora about the Go Green Week at Samuel Staples Elementary School, my daughter and I spent some time preparing. One way I’ve found to be effective in bonding with Maddie has been to engage her artistic spirit. So, on a Friday evening, we made colorful fractal patterns of photos I had taken of some nearby trees. We spent a lot of time changing the colors. My daughter is very particular about which shades classify as ‘pink.’ Eventually, we got the code right, and then used the resulting image set to some Katy Perry music (California Gurls) for a social media post.

It’s a fascinating time of year in the lifecycle of trees. As buds form ahead of the leaves, it’s almost as if the tree is inhaling deeply. Soon, its leaves will exhale oxygen and “eat the photons” as I tell my kids (to eye rolls) from the sun. In doing so, they pull C02 from the air and store it as biomass. That got me thinking, if I can use art and nature to bond with my daughter, I might as well try to convert it to science as well. We were already using artificial intelligence for the art project, Cursor, an AI-enabled development program, so why not expand it to the sciences?

Just like AI helped us edit the tree’s fractal patterns to my daughter’s lofty standards, it can be used to help us map, model, and restore tree cover. Trees function as carbon sinks, create temperature-regulated microclimates, support biodiversity, and improve the soil’s water retention. Easton’s tree-lined streets add to the bucolic atmosphere, give employment opportunities to tree-service workers, and put on a show nearly every fall. What, after all, would Easton be without them?

A recent paper in Nature Scientific Data used AI to explore the concept of tree cover carrying capacity (TCC). The authors utilized the measure to estimate the long-term average tree cover an area can support under current conditions, but excluding human impact. Essentially, they’re asking “How many trees would thrive here if nature was in charge instead of people?”

The analysis is conducted at a resolution of one kilometer. To prepare the data, the researchers took steps like removing all cultivated land, urban areas, bodies of water, and several other variables to avoid misleading results. This data cleaning process ensures the AI focuses only on areas where trees would grow naturally, creating a more accurate estimate of the ecosystem’s TCC.

Once the data is cleaned, the AI is trained. In this case, the researchers used random forests and quantile regression forests, pun most definitely intended. The AI, in other words, learns to see the trees, and the forest.

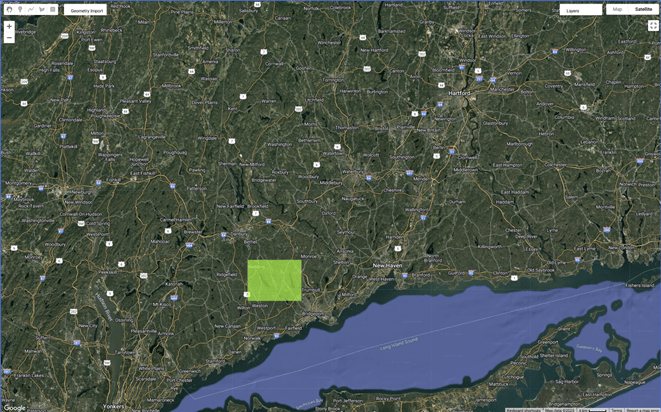

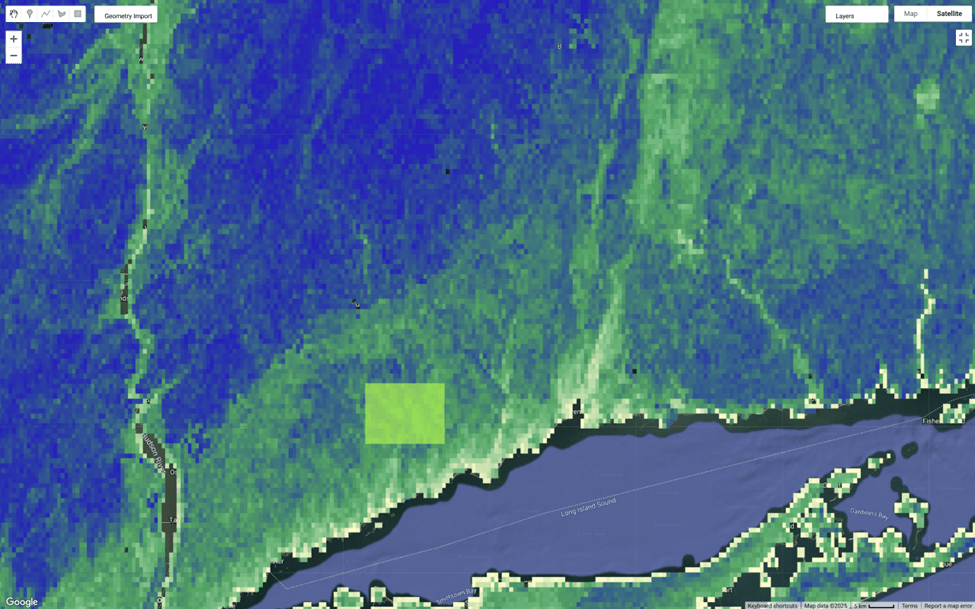

So, what does this mean for Easton? For one, it means we can use AI to put filters on photographs of trees. We can also use the online tool to access the data which is publicly available. Here is the base layer, a satellite view of Easton, in the green box, and the wider region.

And here are the results. In terms of local tree potential, it’s difficult to be precise. Remember, the resolution is 1,000 km. But one thing is immediately clear. If nature were left alone, tree cover would increase significantly. Of course, trees aren’t going to be popping up anytime soon, people are still here. But what if we chose to help nature—by planting trees where they’re most likely to thrive?

This idea isn’t theoretical. The Aspetuck Land Trust is already putting it into practice. Through their partnership with the City of Bridgeport, they’ve planted over 3,000 trees and shrubs near the city’s schools since 2013. They use the Miyawaki Forest Method, where trees are planted close enough to compete but far enough to allow everything to thrive without a single species dominating. This makes these small forests biodiversity hotspots.

It makes them more resilient.

Strategically located near schools, the trees not only clean the air but offer outdoor learning opportunities, turning every sapling into a science project in progress.

Artificial intelligence is reshaping many aspects of our lives. Using it to estimate potential tree cover is just one example of how we can combine information technology, ecology, and imagination to shape a better future.

Take a second look at the trees you pass each day. Notice the fractal patterns on barren branches, or the subtle glow of leaf buds ready to burst open. Think about the interconnected networks growing above and below the surface. Make them a part of your family, as I have with artistic pursuits with Maddie.

The future of our forests may depend not just on what we see, but on how we choose to act. This Earth Day don’t forget to support the trees, or your local land trust!