The wood thrush calls are so loud, I can hear them over Taylor Swift playing for my daughter in the back seat. We’re on the way home from a dinner date at the Monroe Diner. After a long fun day of gardening, including planting new native anchor species in our food forest in progress, the Diner hit the spot. On the way home, we followed some new signs we had noticed along Sport Hill Road about protecting the watershed. Don’t break zoning, the signs read.

It’s the flute-like staccato call that immediately lets me know we’ve entered a different ecosystem. In lower Easton and aside route 136, the noise from the increasingly busy roads drowns out these beautiful calls. It’s on windy roads in the forests that the wood thrush hops about. Once, on Everett Road where there’s turnoff parking for reservoir access, a wood thrush crossed the road, unbothered by my stopped car, its chest proudly puffing in and out in rhythm as it strutted across the pavement.

Luckily for the wood thrush, my trip through the woods was not rushed, and I spotted the jaywalking bird. Easton’s forests are mostly owned by Aquarion Water Company, but there are some state and municipal tracts. Private residences can also have forested lands, with some designated like farms as 490 properties (as in, Public Act 490) with the state. Our forests offer a place for residents to slow down. For many, they’re part of what first attracted us to the area.

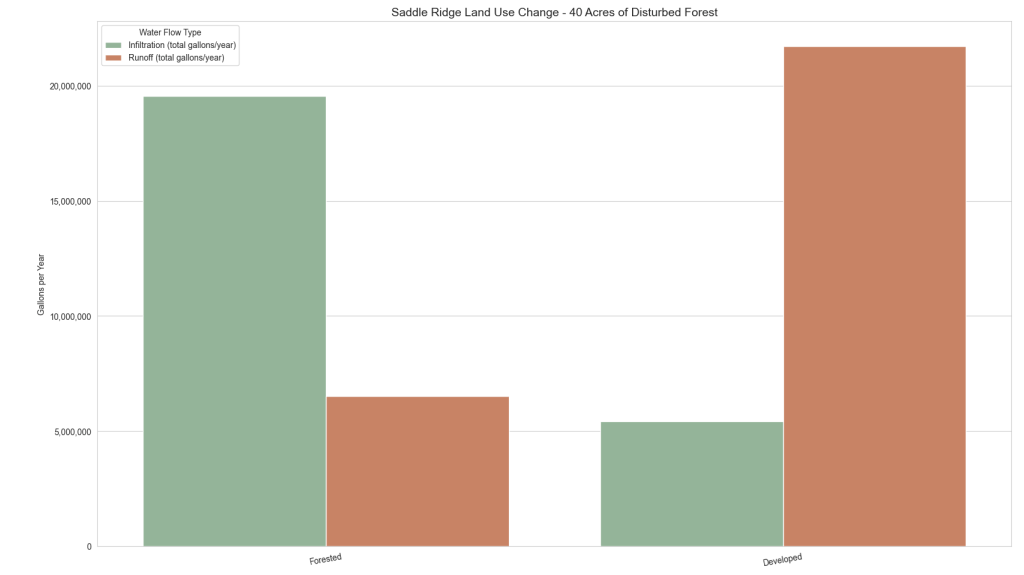

But, people and cars aren’t the only thing these forests slow down. They also play a major role in slowing down stormwater runoff. Forested areas like this can act as biotic pumps, releasing water vapors and aiding cloud formation. The types of clouds, and the water cycle, are almost as complex as the networks of mycelium running along the forest floor. The local water cycle in action, as systems work holistically to support life for all of us.

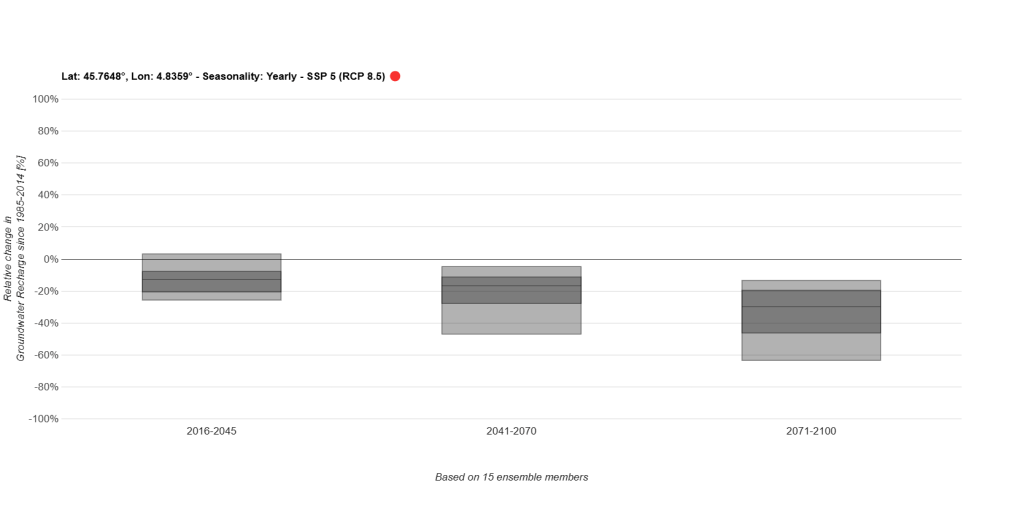

What, I wondered, would protecting the watershed, and forested areas like Saddle Ridge, look like as the world warms? Luckily for me, recent news brought a new tool from French researchers and company AGEOCE, “Explorer for Climate Change Impacts on Water Resources” which gives a glimpse into the watershed’s future. The tool allows you to see predictions from high-resolution climate models using watershed-specific hydrological data under various warming scenarios. The results for Easton are sobering.

Under moderate scenarios, the projections show a decline in summer streamflow and decreased groundwater recharge. This would put steady pressure on wells, wetlands, and the ecosystems they support. As the century continues, the stress on the aquifer becomes more acute. Under high-emissions scenarios, Easton could see a median 27% drop in groundwater recharge by 2100. That kind of loss would alter the local water cycle, and our ecosystem, with potentially drier forests, earlier seasonal dieback, and the potential disappearance of relatively sensitive species like the wood thrush. That’s a song that would be missed.

And, when groundwater recharge drops, Easton’s reservoirs receive less inflow, evaporate faster, and grow more vulnerable. Protecting the forest means protecting nature’s spigot.

Temperatures are rising, and it’s helpful to have forests to keep us cool. They stabilize the watershed by aiding recharge into aquifers and decreasing runoff and erosion. Already, embankments along Sport Hill Road are showing signs of this wear from runoff. Change and erosion are, of course, the only consistent part of life. What would a change in this ecosystem mean for the wood thrush?

According to a January 2017 hydrological evaluation of the Saddle Ridge property, under normal rainfall, groundwater recharge at the 110-acre site would total just over 57,000 gallons per day. In a 30-year drought, that drops to about 40,000. The models assumed septic systems return 85% of used water back into the soil, but didn’t factor in the bigger picture: less rain, more pavement, hotter days. Every one of those will work against recharge. And when the water stops sinking in, the system’s beautiful feedback loop breaks down. Forests dry. Streams start to fade. The damp, shaded undergrowth in which the wood thrush seeks shelter and subsistence could disappear, along with its haunting, fluted song.

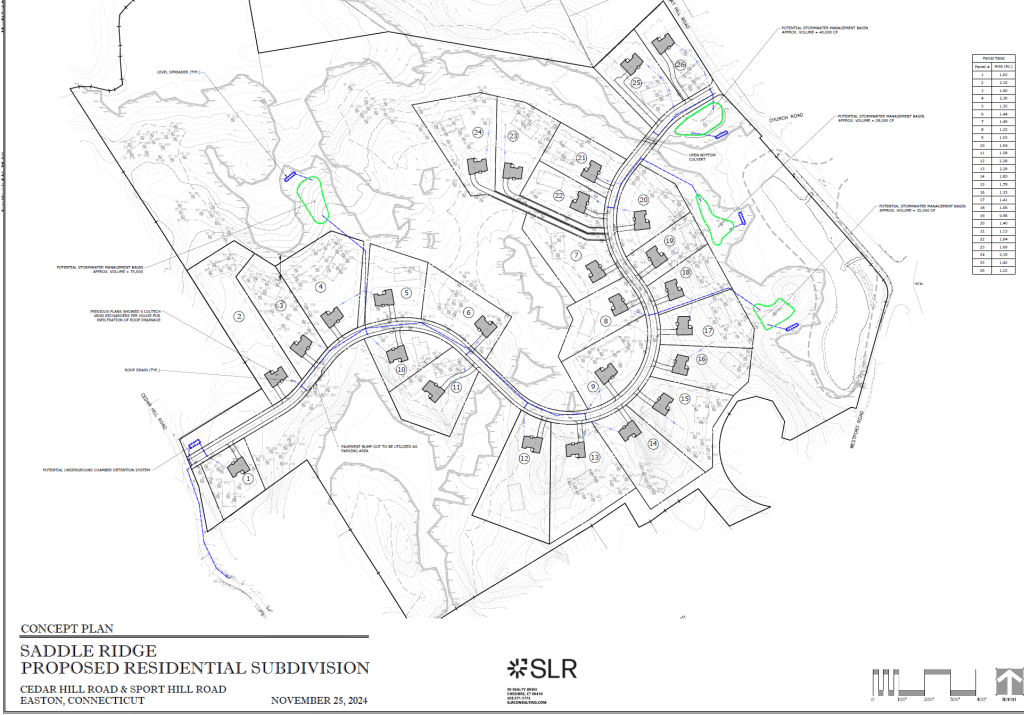

The current proposal, for 26 homes, each with its own septic and well, would replace 40 acres of intact forest. The ‘preserved’ open space left behind would consist mostly of fragmented wetlands, tucked away behind McMansions. Pitched as the town’s first use of Section 5900, or ‘Conservation Development Zoning,’ it remains unclear just what is being conserved. The project bypasses Easton’s traditional three-acre zoning, fragmenting a wild habitat and hardens the soil to the watershed’s detriment.

Some may argue that building fewer homes with newer technology softens environmental impacts. But the truth is, it’s the land use change in and of itself that sends shockwaves through the local water cycle. The clearing of trees for foundations, carving roads and driveways through the once spongy forest floor all take their toll. The 2017 hydrologic evaluation for the site shows how delicate the property is, even under normal rainfall assumptions. Sprinkle in a future of longer droughts, more erratic and intense storms, and ever-increasing heat.

Simply put, strip the forest, and you lose the very anchor of a system that slows, stores, and recharges water.

Soil starts to dry out. Evaporation speeds up. Rain runs off instead of soaking in. Land that once functioned as a quiet recharge pump becomes a source of stress. If you want to protect the watershed, follow the signs, and listen to the wood thrush calling from the stillness off Bibbins Road.

Protecting the future of the watershed means protecting forested lands like this one, today. It means fully accounting for the natural services the land provides when considering its future use. Yet, protection doesn’t have to mean paralysis. Our community does have unmet needs, affordable housing being chief among them. Seniors who have lived in town their whole lives may struggle to maintain their property and stay in their homes. What if, instead of carving up this ecologically valuable land into luxury units for a quick profit, we ask any developer how their project can better serve people and the planet.

This parcel could signal the start of doing things regeneratively. It can be restored where needed, kept wild enough to maintain ample habitat, and maybe one day host modest housing on existing cleared spaces for the town’s seniors looking to downsize. There are, in fact, ways to meet human needs without sacrificing the systems and connections that make life extraordinary. We don’t have to choose between community and conservation; we must design with the intention of both.

The question is: are we willing to listen? To science. To the land. And maybe even to the wood thrush, still singing—loudly for now—from the untouched forest.

References:

Attard, G., Müller, L., Bardonnet, J., Kneier, F., Döll, P. (2025) Explorer for Climate Change Impact on Water Resources, Version 1.0: [http://ageoce.com/en/apps/climate-change-water/] AGEOCE.

Old Growth Forests – Nature’s Biotic Water Pump, YouTube: [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FtGRjAIr8Zg]

Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection. “Connecticut Stormwater Quality Manual.” Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection, Mar. 2024, [https://portal.ct.gov/-/media/deep/water/water_quality_management/guidance/swm_mar_2024.pdf?rev=1dafea8e03ca4ec98f5ec011d803f4dc&hash=A49802ED8F721C491C85776C3E77CF51]