Carbon is everywhere. It’s in the trees that line our streets and the soil in which our farmers grow their wares. We too contain carbon in our bodies. And here in Easton, where the Aspetuck, Mill, and Saugatuck Rivers cut through ancient stone and quiet forests, the story of carbon stretches back not just decades, but millennia.

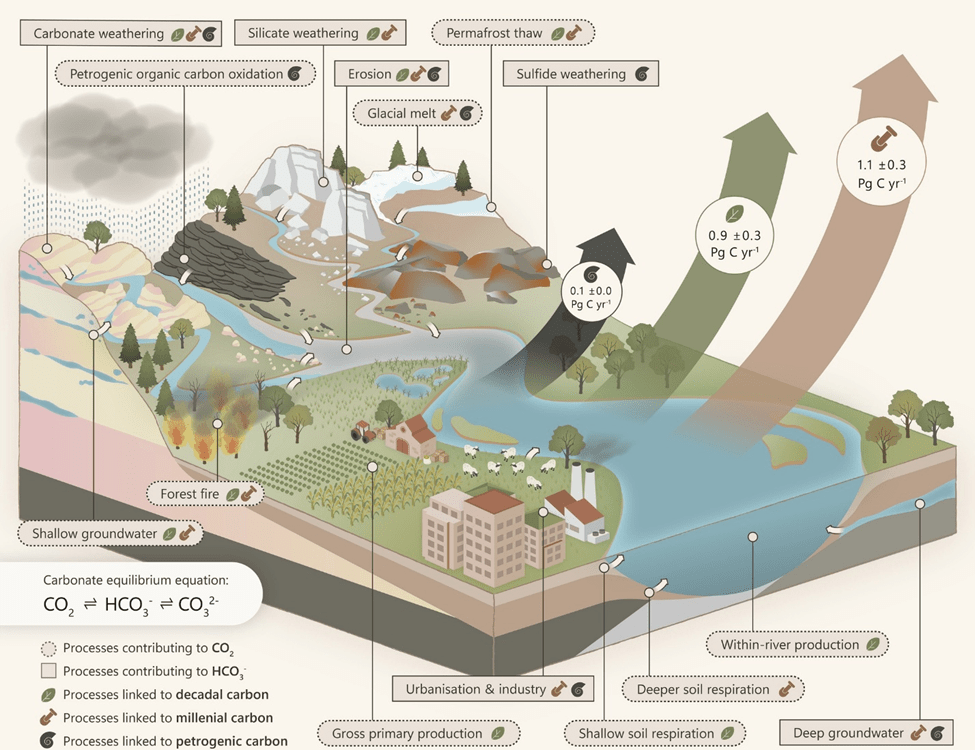

Recent research published in the journal Nature, has revealed something surprising, nearly 60% of the carbon dioxide released into the air by rivers each year isn’t from decomposing leaves or modern runoff, it’s from carbon fixed hundreds to thousands of years ago. Ancient carbon. Fossil memory. Stuff that has lingered underground since long before asphalt roads or colonial land deeds, now being breathed out into the warming sky. The scientists did not think the water cycle worked in this fashion.

The finding upends the conventional wisdom of the water cycle. These rivers, in other words, are not just moving water. In a way, they are releasing time. Easton is full of time, especially if you’re willing to take the time to notice.

Over 100 prehistoric archeological sites have been identified here, many of them centered on the river valleys that have sustained life here for more than 10,000 years. Early peoples likely settled near what we now call Crickers Brook and the Aspetuck River not just for fish or game, but because these landscapes offered something deeper, continuity. A pattern of cycles: of water, of food, of carbon. Of life.

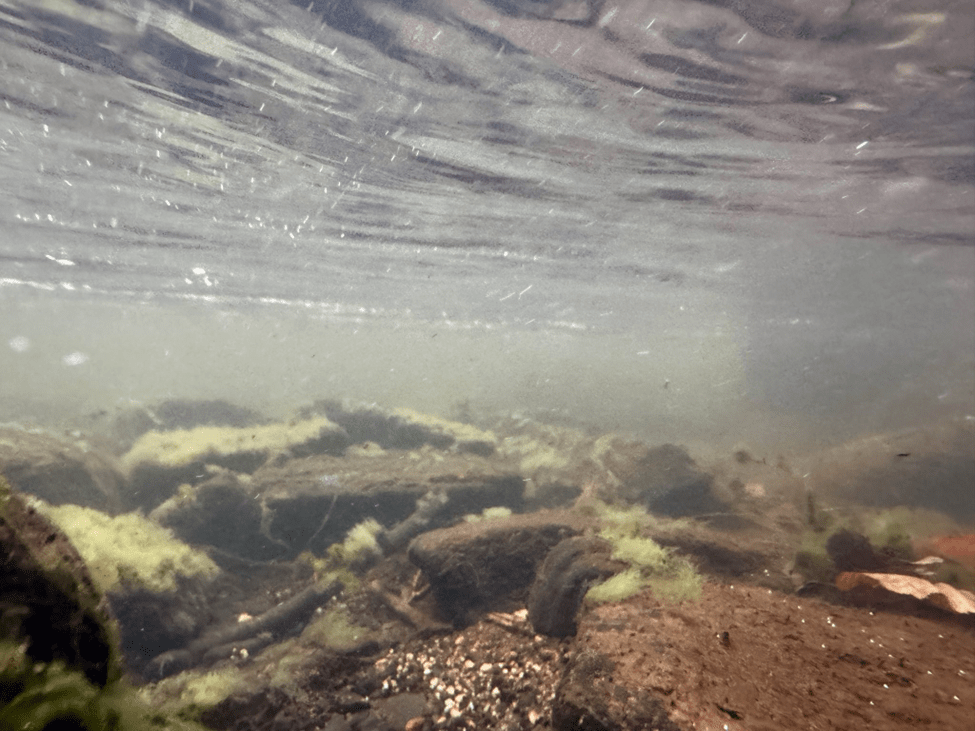

As someone who has spent countless hours in or around the Mill River on a quiet afternoon to meditate and connect with nature, I can tell you: the river water holds stories. And now, science is catching up to what Indigenous knowledge has long understood, that the Earth is always speaking, if we learn to listen.

The carbon that flows out of Easton’s rivers on a hot summer afternoon may have started its journey hundreds of years ago, fixed from the air by a tree whose rings now lie deep beneath the forest floor. Carried down over time through soil, stone, and into aquifer, disturbed by erosion or the march of progress, it eventually makes its way to the surface, rising again as if to breathe. A deep exhale, not from us, but from the Earth itself.

In this way, the old and the new are not so separate.

This can shape the way one thinks about conservation. It’s not just about protecting bucolic views or wildlife corridors, though those matter greatly. It’s about acknowledging the long memory of the land. When we alter wetlands or dam a streambed to make way for development, we do more than reshape the landscape. We’re disrupting the natural rhythms formed over thousands of years.

Easton’s character is often spoken of in terms of historic houses, farms, New England stone walls, and quiet forest roads. But perhaps just as important is our relationship to the unseen: to the carbon below our feet, to the slow time of rivers, and to the forests that act not only as lungs but as living regenerative systems.

The 2006 Town Plan of Conservation and Development made it clear that Easton’s heritage, both prehistoric and historic, is vital to the town’s character. What wasn’t as clear then, but has since come into focus, is how deeply this heritage is tied to the Earth’s own metabolic processes. We are not separate from the carbon cycle; we are part of it. And Easton’s rivers remind us that the past isn’t past. It flows right beneath us.

As the planet continues to warm, and land use continues to change, more of this ancient carbon will be mobilized, released not in some faraway Amazonian rainforest, but right here, quietly, as water trickles over rocks in mid-June.

So, what can we do?

We can begin by protecting riparian buffers. By respecting wetlands. By listening to science and seeking indigenous wisdom. We can ask our elected leaders to integrate deep time into planning decisions, to see each available parcel not just as acreage for development, but as an archive for future generations.

A history lesson that explains our collective response when faced with the immense pressures of the “present moment of the past.” (h/t: Maria Ressa)

And perhaps most importantly, we can grow deeper roots here, not just in physical space but also in time. The time spent walking the trails near the Mill or Saugatuck River to wonder what lies beneath. To feel the chill of crystal-clear river water and imagine the centuries that brought it to your hand. To slow down enough to know the land not as passing backdrop, but as witness. To inhale deeply as the river exhales.

The Earth remembers. Will we?

The study:

Dean, J.F., Coxon, G., Zheng, Y. et al. Old carbon routed from land to the atmosphere by global river systems. Nature 642, 105–111 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09023-w